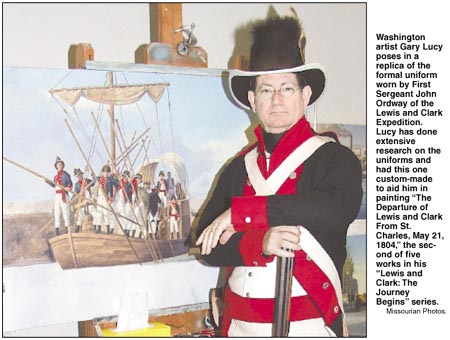

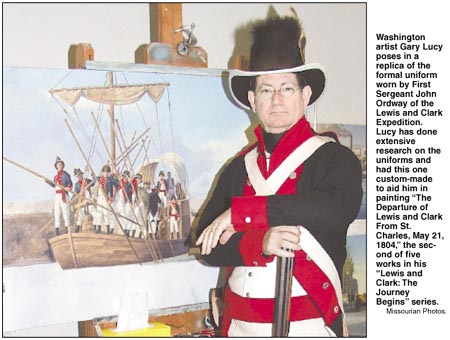

Gary Lucy strides around his Washington art studio wearing

a formal uniform like the one First Sergeant John Ordway of the Lewis and

Clark Expedition would have worn when the group departed from the St. Charles

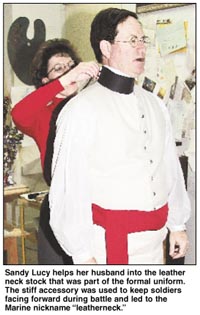

riverfront in 1804. As he adjusts the red silk sash imported from England

that is now wrapped around his waist,

the famed artist explains the accessory's purpose.

"The sash was a distinction of rank,"said Lucy. "Officers

had the privilege of wearing a sash.

The sash on officers was much larger than this one and

made of very strong silk. The purpose was, if officers were killed in battle,

they could

be carried out using the sash."

Placing a bear fur accented hat on his head, Lucy noted

another distinction on his Ordway-replica uniform—the epaulets on the shoulder.

"That meant that he was the first sergeant,"said Lucy. "Stripes didn't

come into use until the War of 1812."

The Ordway costume is at the heart of a painting Lucy

is now working on, "Departure of Lewis and Clark From St. Charles, May

21, 1804."The piece is the second of five in a series, "Lewis and Clark:

The Journey Begins,"which focuses on the expedition's first 70 miles up

the Missouri river.

Before ever putting brush to canvas, Lucy began this

current project by researching what information was known about the expedition.

He didn't just study the facts, but dug deep to uncover the details other

historians might overlook, like the color of a boat and what clothing they

would have worn at a certain departure.

With regard to that clothing . . . he didn't just go by

what other artists or costume designers before him said it should look

like. He found out for himself. Much of the information was provided by

the National Army Archives Museum in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where the

costumes were actually made according to the original pattern text—"The

coat shall be navy . . . the epaulets shall be . . . "

"This has been heavily researched,"said Lucy, gesturing

to his outfit. "To my knowledge, it's as close as possible to what their

uniforms would have looked like. "It's all hand stitched and with the type

of stitches they would have used then (in the early 1800s),"he said,

also noting that the coats were made cheaply, for about 80 cents.

Getting the details right in these types of paintings

is almost a necessity, said Lucy, who began doing historical interpretation

works in 1986. His first piece was of the St. Louis

riverfront in 1886.

"I dug around as best I could to find out what the boats

looked like,"he said. "But afterwards, I got calls from people saying it

wasn't right. Then there were other people who wanted to use the piece

for this or that . . ."That's when I realized, if these were going to be

used for educational purposes and could find their way into history books,

I'd better know what I'm talking about.

"There's more that goes into these paintings than just

sitting down and picking up a brush,"he remarked. |

The point of having uniforms and other clothing items

custom-made is more practical than just to have a visual prop. It's also

to gain a more accurate understanding of how the uniform would have moved

when the men were doing such tasks as rowing.

To get that understanding, Lucy actually puts on the costumes

and has photos taken of him in certain poses. He then uses those photos

as a reference when painting a scene. "I take about 50 photos for each

person in the painting,"said Lucy.

"Then I pick one to refer to . . . it lets me see what

would really have gone on with the uniform, like how the coat might ride

up on a certain maneuver."

Just as he ordered replicas of the uniforms and fatigues

worn by members of the expedition, Lucy also commissioned a model of the

keelboat they traveled in from Blair Chicoine, of Sioux City, Iowa, who

has since passed away. Chicoine built all of the boat models displayed

at the Lucy gallery.

To learn as much as he could about the Lewis and Clark

Expedition, Lucy began by attending several national conventions organized

by the National Bicentennial Committee, where he met and talked with other

historians, like Steven Ambrose, on the subject. One of the more helpful

historians Lucy worked with was Bob Moore of the Jefferson National Expansion

Memorial (the Arch) in St. Louis.

"I've talked to a lot of people, experts in the field,

and learned a lot of information,"said Lucy, "right down to the men's shoe

sizes.

"I've wound up learning more about Lewis and Clark than

I ever dreamed I could,"he remarked.

For instance, he knows the interior color of Lewis' coat

was white, while that of Clark's was red. The only African-American on

the journey, York, was Clark's slave. And Lewis' dog, a Newfoundland named

Seaman, was onboard.

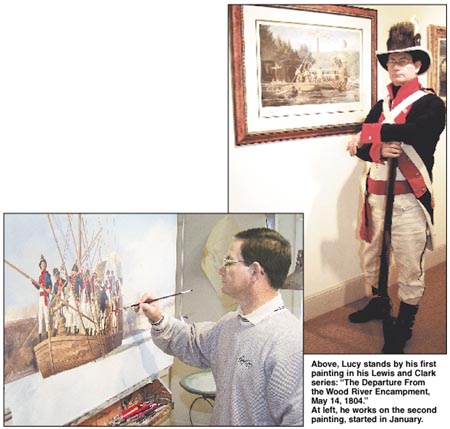

Of all the research Lucy did for the Lewis and Clark series,

so far the most interesting has involved the flag flown from the keelboat.

It was "the most laborious issue"of his first painting in the Lewis and

Clark series, "The Departure From the Wood River Encampment, May 14, 1804." |

After studying drawings of the flag by Clark in his journals

of the trip and receiving feedback from other historians, Lucy decided

the flag included an eagle in the canton area with red and white stripes

below and a white pennant on the right side.

In addition to researching the specifics about the Lewis

and Clark Expedition, Lucy has studied up on the people and events surrounding

the journey.

"To understand Lewis and Clark, you need to understand

President Thomas Jefferson, Napolean, the transportation methods of that

period and things like, was it more likely that a bolt of fabric would

come in 54 inches or 36 inches . . . because it all fits together."

For Lucy, knowing that last bit of information makes the

difference between whether coats ordered for recruits on the expedition

would have been short or long.

"Accuracy is like a web that weaves itself around a subject,"he

remarked, chuckling a little as he thought of the situation's irony. "History

was never one of my favorite subjects,"he recalled, with a smile. "When

I was in school, my worst grades were always in history class, and studying

history was always the furthest thing from my mind."An artist, first and

foremost, Lucy also is a unique type of historian.

"Typically, historians either lecture—they give an oral

interpretation of a subject—or they put things down in a text format. What

I have done is put that same history on canvas to actually show what it

would have looked like,"said Lucy.

"Historians can say ‘Lewis and Clark used a keelboat,'

and not worry about what color it was or what it looked like. But when

I make that step from text to visuals, I have to, within reason, be able

to see it to paint it.

"The most perfect thing an artist can do is interpret

what is in his mind . . . it goes down to your hands and comes out here,"said

Lucy, wiggling his fingers. |

|